Source: WCAX, Scott Fleishman

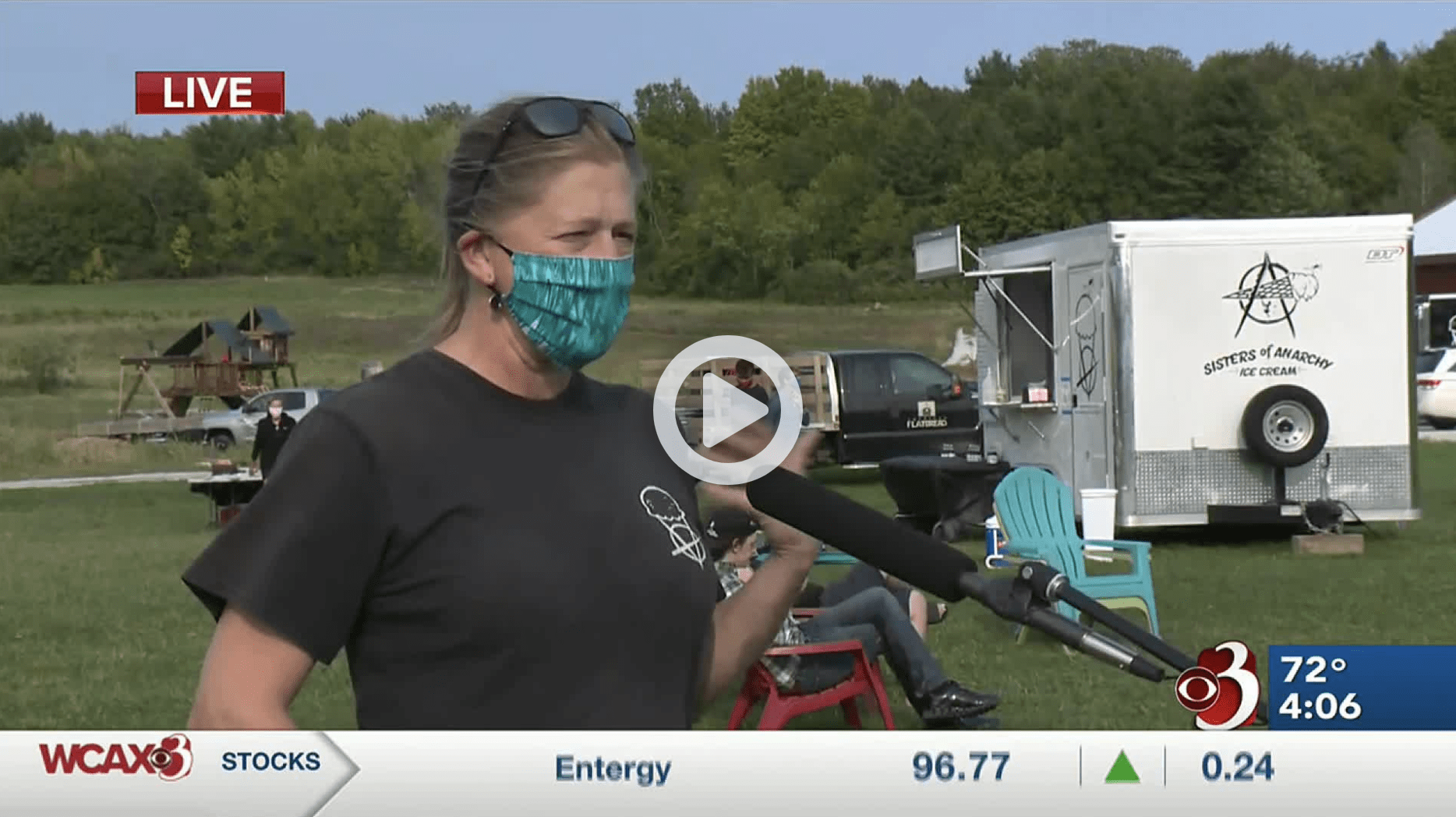

SHELBURNE, Vt. (WCAX) – Ice cream and pizza were on the menu at Fisher Brothers Farm Wednesday.

From 4 p.m. to 7 p.m., Sisters of Anarchy Ice Cream and American Flatbread invited students and their families to take a break from remote learning and enjoy food on the farm. They had the choice to buy a number of different styles of pizza and unique ice cream flavors.

There is also live music and plenty of space to be physically distant.

This is the second straight Wednesday Sisters of Anarchy has hosted this event and are planning to do it again next week.

There has been a progressive reaction toward the industrialization of food. “Natural” became more narrowly defined by “organic” and organic became subdivided between large scale agriculture with continental and global distribution, and smaller more artisanal scaled production with local and regional distribution. The newest development in food production is what has been termed “Nutrient-Dense” or “Deep Organic” food. These are foods that are produced by optimizing soil chemistry and diversifying farm biology. The primary emphasis is on soil structure and nutrients but also includes creating on-farm habitat for a wide range of organisms most of which are greatly beneficial to food crops. Early studies have suggested that crops grown this way are more resilient to pests, are richer in important human nutrients, and conserves and enhances biological diversity. This diversity is foundational to all ecosystems and essential for sustainable agriculture. And because this form of agriculture tends to be more intensive, or more densely planted, it may offer a way to increase world food supplies for an expanding human population without usurping more land for agriculture.

There is much good to be said about Nutrient-Dense/Deep Organic agriculture, and it may well be that it or some form of it will be the most sustainable way to feed ourselves without further degrading the environment, however, it is important to note that as currently practiced it is far more labor intensive than conventional mechanized agriculture; this tends to make food more expensive, and it is unclear if it is scalable, especially for grains which remain, and possibly will always remain, the richest source of human food energy.

I once worked with a man

who had lost his hand

in a fishing accident.

He made do with one.

My Mom made do with one good ear,

which in noisy rooms

was a hard thing to do.

And she made do

working in a small antiquated kitchen

saved by a window

that looked out to a tree

where the robins gathered in Spring.

Today I worked to make do.

I let go of what I thought best

and accepted what was,

understanding there would be other days

for what I thought best.

I know making do

does not ring of victory,

but victory is not

for all things.

Sometimes,

the best we can do

is to make do

as best we can.

It’s just letting go

of our egos.

Thanks for coming tonight.

Love, George

There is a simple stone circle that lies like a heart in the middle of Lareau Farm. The first iteration of this stone circle at was built in the Summer of 1991. What began as a decorative way of storing some extra rock has evolved into the emotional center of American Flatbread.

In early July, 1991 I travelled to Granville, Vermont to check out the much talked about (and worried about) national gathering of the Rainbow Family, a loose knit gathering of old hippies and neo-primitivists. As we got within a few miles of the main encampment I was stuck by the sheer number of people walking along the side of the road. We quickly filled the back of my pick-up truck with hitchhikers and hoppers on which gave us “bus” status and close entry to “camp one”. It was here I discovered one of the best field kitchens I had ever seen. A couple of old tarps tied to dead saplings lashed together sheltered primitive prep tables and two gigantic cast iron cauldrons cradled in an earthen fire pit. Both cauldrons were filled to the brim with stone soup-that is, with any and all, or almost all, vegetables, herbs, etc. from the collected donations of the assembled, and watched over by the master of the kitchen who proudly proclaimed that his was the best kitchen at the gathering and that he would feed close to a thousand people that night. Although somewhat boastful, his claim was accurate. I returned home inspired.

A few days later back at Lareau Farm I shared what I had seen with my landlord Dan Easley who laughed and said, ” you know, there is a big old cauldron up in the barn. You are welcome to use it if you like”.

Time has a way of passing by even the best of intentions and it would be another year before I acted. In June of 1992 I finally got to it and started making American Flatbread’s tomato sauce in Lareau Farm’s big cauldron. I built a fire pit at one side of the stone circle and suspended the cauldron with maple saplings.

At about the same time three other important events occurred.

I.

My earlier studies of Native American architecture evolved into a study of Native American spirituality and it was in this context that I was introduced to the concept of the Medicine Wheel – a lithic structure that encloses a sacred space. One purpose of a Medicine Wheel is to remind those who enter of a power greater than themselves and that what we do and why (our actions and intentions) matter a great deal.

II.

In the Fall of 1992 while in Boston doing a series of in-store demos to promote our frozen Flatbread line in new stores I happened to walk by the Shriner’s Burn Institute for Children. As I looked up at the windows I thought of the kids inside – some of whom were probably the same age as my own children. Their pain and suffering and struggle to get well seemed palpable. My heart ached for them and my head wondered what, if anything, I could do for them. I am neither a Doctor, nurse, physical therapist, or social counselor. Images of the kids up there triggered memories of my own childhood hospitalizations, memories that included hospital food. Yuk!

Maybe that was it. Maybe that was how I could help. Maybe I could make something for kids that would be both fun to eat and good to eat. And maybe, just maybe, it would in some small way help, after all, the building blocks for repairing damaged tissue come from our food, water, and air.

Shortly after I returned from Boston I spent an afternoon in the UVM medical library searching the literature about pediatric nutrition in hospitals. It was a field of study I was unfamiliar with and the specialized language took some getting use to. Because of the technical nature of most of the journals a great many promising titles proved to be reports from intervenous feeding studies. Even in journals written for and by nutritionist and dietitians I found surprisingly few articles concerning whole foods. I did find one however and it confirmed my thesis that good, wholesome, flavorful and familiar foods have a place in the diets of the ill and injured. The article was written by a dietician working at the Miami Children’s Hospital. She reported how hard it was to get her pediatric patients to eat the food prepared in the hospital. Children can be fussy eaters even in the best of times and this behavior is often magnified when they do not feel well. In addition, childrens’ appetites can be supressed because of the unfamiliar surroundings of the hospital, because of the meds they are on, or simply because the hospital food does not look or smell or taste familiar. In extreme cases just getting an ill or injured kid to eat a candy bar is cause for celebration. The article went on to describe how friends and family would often bring in food for the young patients and that often this food was from nearby fast food restaurants. Hamburgers, French fries, fried chicken and pizza, foods the author called “child friendly”, were common and often much more readily eaten by the ill and injured children than the food prepared by the hospital staff. The author of the article lamented the typically poor nutritional value of these foods but acknowledged that in many ways the fast food restaurants were doing a better job of getting the pediatric patients to actually ingest some nutrition than the hospital’s highly trained food professionals.

III.

Also in the Fall of 1992 I began to volunteer at my daughter’s elementary school. Under the leadership of her teacher Roni Donnenfeld we built a maple sapling wigwam on school grounds, and in the Spring put in a garden. The following Fall we talked with the children about making pizza for kids in the hospital. The idea was to make “child friendly food” that was genuinly nutritious. Several of the professional educators questioned whether five and six year olds would be able to make the connection with kids they did not know in a place they were unfamiliar with, but everyone was of good spirit and we decided to give it a try. Together we designed, using large cardboard play bricks for our modeling medium, planned and built a 5000 pound earthen oven. Next, the children helped make a batch of organic tomato sauce in a huge wood-fired cauldron. With this done we made the dough, grated cheese, fired up the oven and then each student in turn baked their own Flatbread. We had a snack of pizza that day and then packed up the rest to take to the hospital.

Bobbi Rood, a neighbor and friend, had gotten in touch with Child Life Specialists at the Chidren’s Hospital at Fletcher Allen (Burlington, Vt.) and together we made a time to come up and do a “pizza party”. I remember feeling a little nervous that first time. I wondered how it would all be received by the children? Their parents? The medical staff?

The paradox of that first pizza party at Fletcher Allen in the Fall of 1993 was the same that would reaccure with every pizza party thereafter: it was both underwhelming and overwhelming. Underwhelming in the sense that there were no balloons, banners, or bands, no fancy kitchen to work out of, hardly anyone of the staff on the floor even acknowledged our presence. Overwhelming because of the profound experience of one little boy. His name was Earnie. Earnie was about seven or eight. Earnie had cancer and he had been in the hospital, this time, for about a week, having chemotherapy.

I heated up the little tomato sauce and cheese pizzas the children and I had made, sliced them into small slivers, which I thought would make them easier to eat, and then stood by in the kitchen while one of the Child Life Specialists took a tray of slices around to the patients’ rooms. In a few minutes Earnie’s Mom came into the kitchen with tears in her eyes. I felt awful. “What’s wrong?” I asked, not knowing what else to say. She smiled as she wiped her tears away, “These are tears of joy” she said. ” The little pizzas are the first solid food Earnie has eaten in four days.”

Thus began the Medicine Wheel Project at American Flatbread. For just about every month since we have gone up to Fletcher Allen Hospital, since renamed the University of Vermont Medical Center, and have done a little pizza party. There is nothing flashy about it, there is no fame, there is no money, but it is good in a way that few other things are.

I am sorry to report that I lost track of Earnie. I do not know how it all worked out for him, or for his Mother who loved him dearly. There are some awful illnesses out there and sometimes, try as we might and pray as we do, the person we love just doesn’t get better. Medicine Wheel Bread is not a magic bullet. It is simply good food made with care and the intention to help. The ill and injured deserve no less and even the terminally ill can benefit from good flavorful food, indeed, food is often one of the last physical joys of the dying.

As to the question of how we moderns, steeped in 400 years of scientific rationalism, can understand the role of intention, I would offer that food has a kind of memory – the same memory we understand in quantum mechanics: that we can not observe something without.